Any encounter between police and civilians has the potential to go awry (SN: 11/17/21). Stop and frisk, where police pat down pedestrians suspected of carrying contraband, can be particularly fraught, leading to some efforts to limit the practice.

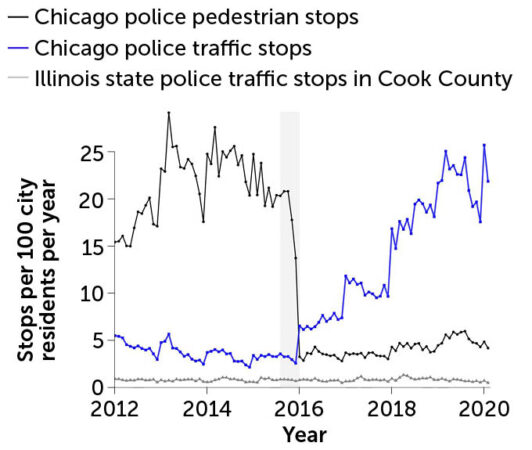

But simply curbing foot stops may not reduce the likelihood of such contentious encounters, suggests a case study of Chicago. A steep decline in pedestrian stops in the Windy City eight years ago coincided with a lasting spike in traffic stops, researchers report September 29 in Science Advances. While the rate of pedestrian stops plummeted by roughly 80 percent over five months in 2015, the rate of traffic stops grew by about the same amount over the next few years.

“This is a really dramatic shift in police activity,” says political scientist Dorothy Kronick of the University of California, Berkeley.

The analysis doesn’t prove that the change in pedestrian stops caused the subsequent spike in traffic stops; nor does it delve into the implications of the change. The Chicago Police Department did not respond to a request for comment.

But the data do suggest that studying a single change might not tell the whole story about police tactics, the researchers say. “We want to … think about the way that police agencies or other government agencies are going to respond strategically to these changes,” says Kronick, who coauthored the study with Berkeley immigration and criminal law expert David Hausman.

Stop-and-frisk policing peaked in popularity in the United States during the 1990s and early 2000s before declining in the 2010s as the practice’s ill effects became clear, researchers noted in January in Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice. Officers disproportionately targeted Black and other minority populations, the practice reduced well-being among affected residents and crime did not drop by as much as expected.

Pedestrian stops plummeted in New York City from roughly 700,000 stops in 2011 to fewer than 25,000 stops in 2015 — a 97 percent drop. In 2015, the American Civil Liberties Union of Illinois released a report showing that the rate of pedestrian stops in Chicago was quadruple that of pre-reform New York City. That report prompted the Chicago police to require more stringent documentation of pedestrian stops.

“A stop that might have taken two or three minutes now took 20 with the appropriate paperwork,” administrators for Second City Cop, an anonymous blogging site for Chicago police officers, explained in an email to Science News.

The impact of that policy change was stark: As of August 2015, Chicago officers were stopping more than 20 pedestrians for every 100 Chicagoans per year, the new study reports. Five months later, that rate had dropped to less than 4 out of 100. The proportion of Black civilians stopped remained the same, at about 60 to 70 percent.

Traffic stops over the next four years, meanwhile, climbed. In 2016, Chicago officers were stopping roughly 3 drivers out of every 100 residents per year. Three years later, they were stopping roughly 22 out of 100, Kronick and Hausman report. The demographics of stopped drivers shifted, from 45 percent Black in 2016 to 60 percent Black in 2019.

Police beats once marked by pedestrian stops saw the greatest increase in traffic stops, the authors note. They did not observe a similar jump in traffic stops among Illinois State Police, whose jurisdiction partially overlaps with the Chicago police, or among neighboring suburban police departments.

The findings don’t surprise criminologist Wesley G. Skogan, who observed the same substitution while researching his 2022 book, Stop & Frisk and the Politics of Crime in Chicago. “When you work with the data, you certainly notice the shift from one to the other,” says Skogan, of Northwestern University in Evanston, Ill. “The crux of this paper is that policing strategies are to a certain degree fungible, that is, you can switch from one to the other.”

Showing cause and effect, however, is tricky. In the new study, Kronick and Hausman draw on posts and comments on Second City Cop suggesting that officers understood that they were supposed to make this substitution.

Current blog administrators concur, noting that the shift to traffic stops seemed like a clear change in policy.

For an observational study, the methodology is sound, says criminologist David Weisburd of George Mason University in Fairfax, Va. Ruling out all the underlying reasons for the switch is impossible, though. For instance, were there other changes within the police department that led to this shift in priorities? Were residents demanding proactive policies to thwart crime?

And the dramatic rise in traffic stops alone raises questions, Weisburd says. “Why would you switch to traffic stops that have the same problems for the public and greater safety problems for police officers?”

Evidence for similar substitutions in other cities is scant. But the push for proactive policing to thwart crime suggests this sort of switch may not be unusual.

“From research, we know that proactive policing is really the best way to manage crime and manage problems in communities,” says criminologist William Sousa of the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. But the line between problematic stop-and-frisk practices and proactive policing, where police increase surveillance in high-crime neighborhoods to keep residents safe, can be fuzzy, he says.

And how to prevent racial profiling in proactive policing remains a thorny question. For instance, the authors of the new study cite a 2019 news story in the Los Angeles Times describing how the city’s police drastically increased driver stops to root out people carrying guns or drugs. As with antagonistic foot stops, police disproportionately targeted Black civilians, leading one lawyer to dub the practice “stop and frisk in a car.”

The study raises many questions, including about the generalizability of the findings, why this switch occurred and, crucially, whether the shift reduced problems associated with pedestrian stops, Hausman says. But it illuminates why looking at a single change in police tactics could cause researchers and policy makers to miss whether the change worked as intended.

“It’s important to take this first step,” Hausman says. “It’s very easy to assume that reducing this particular type of police-civilian interaction will reduce police-civilian interactions overall.”

+ There are no comments

Add yours